Some countries in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) are exploring a variety of options in their attempt to collect additional tax revenues to confront the COVID-19 emergency. With a somber forecast ahead, the region´s GDP may contract up to 6% while the fiscal deficit can climb up to 8% by the end of 2020. In this scenario, tax amnesties emerge as a way of generating short-term revenues, which is why it is paramount to study their possible effects in the light of international evidence.

What are tax amnesties?

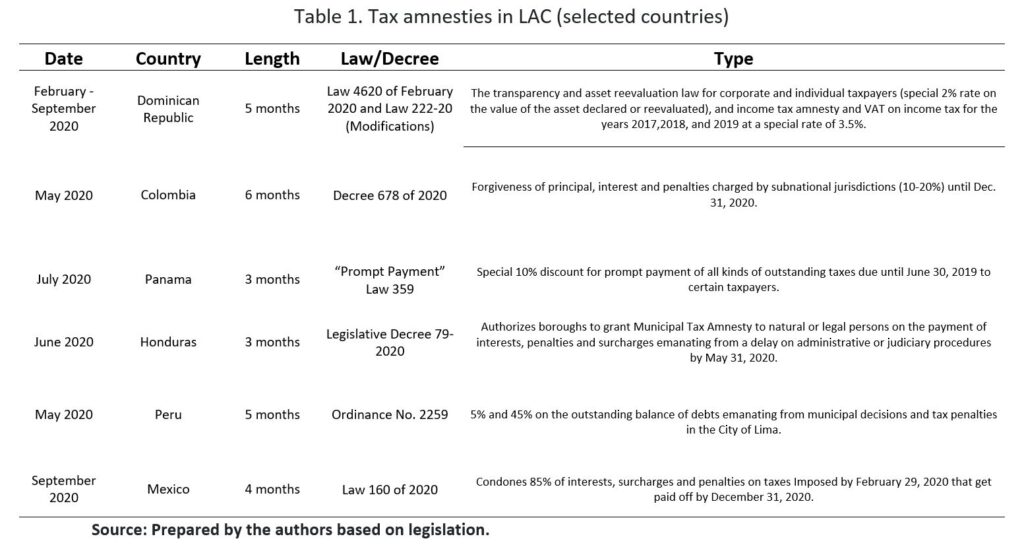

An amnesty is an exceptional and temporary opportunity to regularize taxpayers’ undeclared assets and unpaid taxes (from one or more previous fiscal periods) in exchange for a cut in the outstanding principal or the interest or penalties. Typically, they include waiving any criminal and civil proceedings[i], this can be done by type of tax and taxpayer or through an across-the-board approach. Table 1 provides an overview of initiatives recently launched in LAC amid the COVID-19 emergency.

The use of tax amnesties is not new in the region. LAC has made ample use of them in recent decades for several purposes, including:

- collecting tax revenues in the short run,

- regularizing “clean slate” tax situations of taxpayers with a low or null compliance history,

- improving asset transparency by signing tax information exchange agreements (TIEAs),

- mitigating acute currency devaluation episodes that require capital repatriation incentives, political means, etc[1].

Tax amnesty pros and cons

Tax amnesties have advantages and disadvantages. On the one hand, there is the potential for additional tax collection due to delinquent or non-filing taxpayers’ regularization. Also, it can help broaden the taxpayers´ base in the medium term due to new data collected as more taxpayers normalize their situation. Also, tax amnesties typically do not alter the tax structure (namely, the tax base and rate) because of their temporary and exceptional nature. On the other hand, evidence suggests that in the long run, a frequent use of tax amnesties creates a moral hazard problem, as taxpayers that frequently honor their obligations can view the move as a reward to evaders, who are allowed to pay off their dues in more favorable conditions and with only minor penalties. A credibility dilemma emerges that may lead taxpayers to conclude that the cost of evading is not high and that not paying levies may be the best possible option. This situation creates perverse incentives for tax compliance, which has a negative impact on fiscal revenues in the long run. Furthermore, tax amnesties also affect both fiscal efforts and tax equity, to the detriment of taxpayers who regularly comply with their payments and come away with a feeling of being shortchanged.

Empirical evidence also indicates that the abuse of amnesties undermines their impact over time since their regular use may lead taxpayers to adapt their expectations and behavior and always wait for a new condonation. These dynamics weaken the tax system by exposing tax authorities’ limited capacity to detect and punish noncompliance and enforce rules.

A glance at empirical evidence: Once never seems to be enough

In some cases, governments have found it hard to limit themselves to just one amnesty, as suggested by recent experiences considered the “most successful” in terms of tax collection and declared gross value. This is the case of Argentina (2016), Indonesia (2016), Italy (2009), Brazil (2016), and Spain (2012).

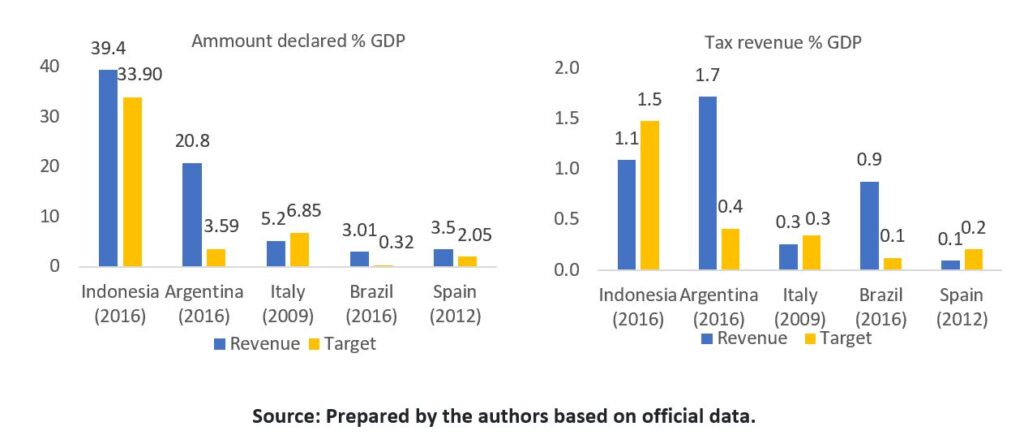

Figure 1 shows the results of these amnesties, which were conceived as exceptional regimes to regularize undeclared or inadequately declared capital, by way of a transitory payment of rates (0% to 15% of income and property taxes), interest and penalties reduction, and opportunities for asset valuation. The results suggest that the most successful one was Indonesia (2016), under which US$367 billion (40% of GDP) in assets were reported and US$11 billion (1.1 % of GDP) were collected in tax revenues. Argentina (2016) is also considered a successful case with US$116 billion assets reported (20% of GDP) and US$9.8 billion (1.7% of GDP) in tax revenues collected. In this case, both the filing and revenue figures were higher than forecasted, making it the country’s most successful amnesty. Results in other countries were lower than these two, yet relatively satisfactory.

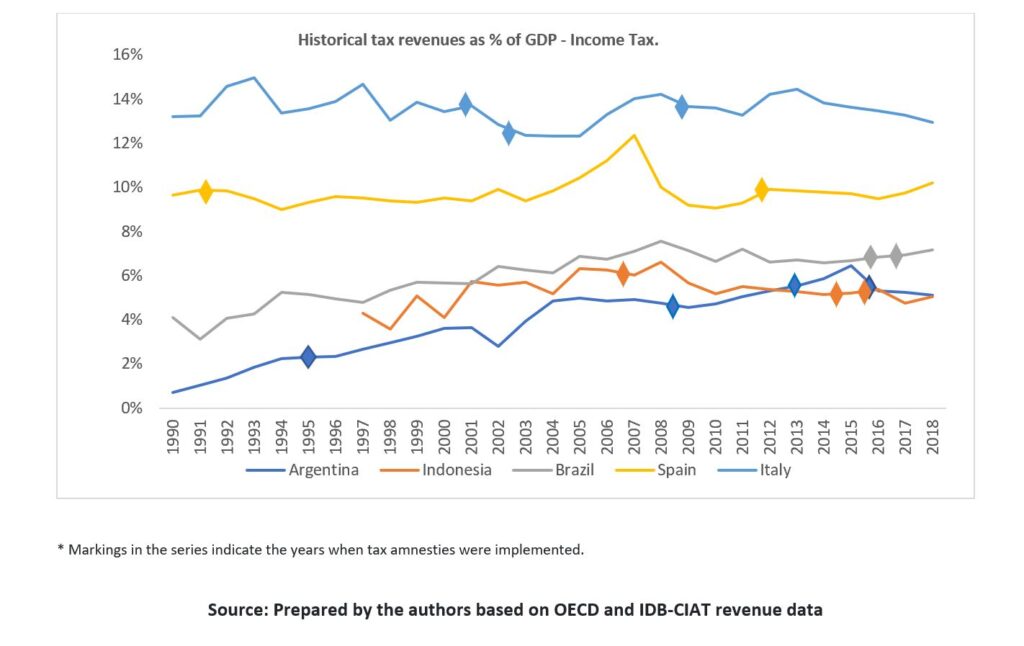

While these amnesties were relatively successful, a deeper look into the evolution of the tax revenue statistics (Figure 2) shows that in most cases, the effects on revenue diluted over time and compliance did not improve in subsequent years. This outcome has repeated constantly over the amnesties that we have analyzed. In addition, some of these measures were highly controversial due to the exceptional conditions offered to non-complying taxpayers, such as not investigating the origin of assets and the capital declared (Indonesia) or the exceptionally low income tax rates in Spain, whose 2012 amnesty was declared unconstitutional in 2017.

Some policy recommendations

Exceptionality and temporality: Tax amnesties are an exception, not an intrinsic resource of the tax system. Therefore, they should be reserved for exceptional times, their transitory status (typically, not more than 8-10 weeks) should be made clear, and the total debt should be covered by the end of this period under the agreed upon conditions (i.e., deferred payments should not be allowed).

Evaluate the net cost and risk of the measure: It is important to evaluate the short- and long-term needs, considering the magnitude of the net revenue losses versus the probability of total loss (which increases as time goes by). It is also worth bearing in mind that an unsuccessful amnesty could undermine the system’s trustworthiness and in consequence its revenues and institutional capabilities.

When designing the measure: It is critical to determine the type of amnesty (e.g. kind of taxpayers and taxes that should be included, benefits granted, etc.) as well as the incentives it generates. Debt forgiveness should be avoided, favoring interest and sanctions reductions instead. In addition, the origin of the capital and income should be checked, whereas persons with fraud- or evasion-related criminal proceedings, as well as public officials, their relatives, and third parties with conflict of interests should not be allowed to participate.

Consider alternative measures: Although they are not perfect substitutes, follow-up activities and payment plans for taxpayers could be considered to boost short-term compliance and increase future revenues. These include installment plans (even in economic crisis environments), extended installment payment options, and permanent programs to promote the voluntary disclosure of infringements.

Strengthen the tax administration system: Ideally, tax amnesties should go hand in hand with structural improvements to boost the system’s ability to monitor and therefore enforce requirements (such as registry, filing, risk management, audits, collection, etc.) and also to tackle tax policy’s weak points (complexity, regressiveness, and high statutory rates). These steps, together with stiffer sanctions for dodgers in the post-amnesty period, have the potential to raise the cost of evasion.