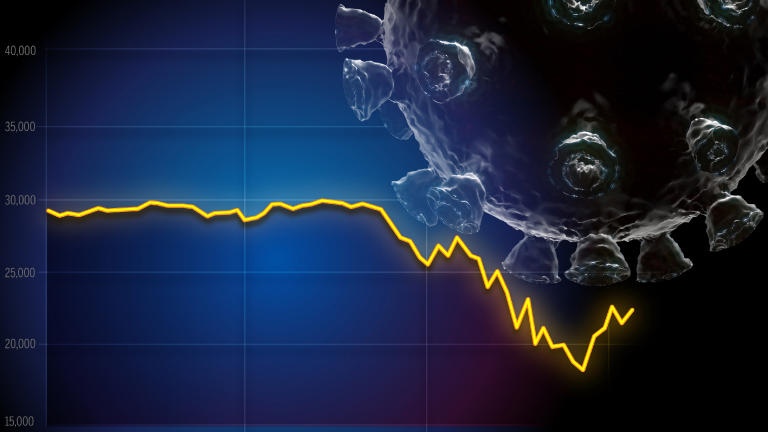

COVID-19 doesn’t just threaten lives, it also puts livelihoods at risk through the destruction of private businesses , which account for 90 percent of employment in developing countries. The lockdowns and social distancing required to contain the coronavirus pandemic have disrupted the activity of otherwise healthy enterprises and their ability to pay creditors. Governments around the world are seeking to support firms through emergency liquidity programs. They also need to review and adjust insolvency frameworks to reflect the unique circumstances of the crisis. This could save more businesses and strengthen the overall path to economic recovery.

The lockdowns and social distancing required to contain the coronavirus pandemic have disrupted the activity of otherwise healthy enterprises and their ability to pay creditors.

Insolvency frameworks are the rules that determine how to resolve distressed assets, so that business activity can continue or assets can be redeployed to more productive uses. Past crises have shown that acute increases of insolvency in small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and of corporate distress—with related job losses—are likely. In developing countries, the damage may be amplified by insolvency regimes that disproportionately result in liquidating firms—even when they are viable—and return less than 30 percent, on average, to creditors.

There’s not only a risk that these rules will promote a destructive wave of premature bankruptcies. Weak insolvency frameworks can also leave so-called “zombie” companies limping along, operating but dependent on rolling over credit, unable to invest in new activity and starving healthy businesses of credit.

A recent report by the Bank For International Settlements (BIS) underscored the magnitude of the threat, estimating that 50 percent of firms do not have enough cash to pay debt servicing costs over the coming year. While many developing economies are at an early stage of the pandemic, they are heavily exposed to its social and economic impacts. The crisis is forecast to lead to the first recession in Sub-Saharan Africa in 25 years, undoing hard-fought progress in reducing extreme poverty.

While many developing economies are at an early stage of the pandemic, they are heavily exposed to its social and economic impacts.

At the same time, as in past financial and economic crises, a sharp deterioration in the quality of assets held by financial institutions is likely. Financial institutions can expect a steep rise in the average non-performing loans (NPL) ratio. For example, at the peak of the Asian financial crisis, NPLs rose to almost 30 percent from 4.7 percent, similar to the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. Given the abrupt and widespread nature of the COVID-19 crisis, distressed assets could be an even bigger problem this time around.

Any response depends on country context, but in general, a staged approach is recommended. In the first stage—where much of the world is now—it is important to “flatten the curve” of insolvencies and use relief measures to prevent viable firms from being forced prematurely into insolvency. Without intervention, even normally effective frameworks may lead to systemic bankruptcy, where a flood of insolvencies could trigger fire-sales and a collapse in asset prices. These relief measures are most useful in emerging markets, where creditors often use the insolvency system as a tool for debt collection.

Without intervention, even normally effective frameworks may lead to systemic bankruptcy, where a flood of insolvencies could trigger fire-sales and a collapse in asset prices.

In the second stage, the key challenge is to respond to the growing number of firms that need an insolvency process to survive. In this stage, it is vital to ensure the smooth functioning of workouts and debt-restructuring mechanisms. It is critical to minimize the number of “zombie” firms, which could starve healthy firms of credit in the post-crisis environment.

Finally, the third stage will require a focus on people coping with personal financial distress in the aftermath of the crisis.

Policy recommendations and country examples

Stage 1: Prevent viable firms from prematurely being pushed into insolvency through time-bound, extraordinary measures

- Increase the barriers to creditor-initiated insolvency filings. Latvia and Turkey have suspended new filings by creditors. Some countries have raised thresholds for initiating a proceeding, while others have limited the right of creditors to apply for the insolvency of a debtor.

- Suspend corporate directors’ duty to put companies into insolvency and the associated liability for failure to file, except in cases of fraud. Directors often have a legal duty to act in the creditors’ interests when a firm is on the edge of insolvency, to prevent businesses from growing debts they will not repay. Spain, Singapore, and Russia have suspended directors’ obligation to file for bankruptcy. Other countries are limiting the requirement under certain conditions, such as insolvency that is directly related to COVID-19.

Stage 2: Respond to the increased number of firms that will not survive the crisis without going through insolvency

- Establish an informal out-of-court or hybrid workout framework. Out-of-court frameworks set out the core obligations for informal debt negotiations with financial institutions, such as a standstill agreement preventing debt enforcement. They can be adopted quickly, ideally driven by the country’s central bank and bankers’ association, and they typically avoid court proceedings. In Albania, the central bank has sponsored an out-of-court framework for banks to negotiate distressed debt with debtors.

- Extend procedural deadlines for a limited time. Insolvency laws typically have short deadlines, because lengthy proceedings reduce creditors’ chances of recovery and foster uncertainty. But short deadlines can force debtors prematurely into liquidation. Bulgaria, France, Poland, Spain, and South Africa have relaxed or suspended numerous judicial and administrative deadlines.

- Suspend requirements to proceed to liquidation, if the business activity of the debtor has stopped while undergoing reorganization. This common feature of insolvency laws aims to maximize creditor recovery, but it may force premature liquidation during lockdowns.

- Encourage e-filings, virtual court hearings, and out-of-court solutions. Many courts are closed. To help them cope with demand on reopening, countries should plan to equip them with more trained staff, put more procedures in writing, and promote digital communication options.

Stage 3: Address individuals’ financial distress resulting from the crisis

Ensure a mechanism for consumer bankruptcy, with appropriate safeguards. These mechanisms, which include those for individual entrepreneurs, provide an orderly framework for paying creditors and give debtors key protections, such as discharge from their debt burden and shielding of certain assets from seizure by creditors. After the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, many emerging markets, from India to Zimbabwe, introduced these critically important tools for consumers and micro-entrepreneurs.

How is the World Bank Group responding?

The World Bank Group, together with UNCITRAL, is a standard setter and the largest provider of financial and technical assistance to developing countries in the area of insolvency. We are helping countries design policies ranging from the rapidly deployable, such as time-limited adjustments to existing insolvency frameworks, to longer-term solutions, like out-of-court workouts, which have been an important tool in past crises.

SMEs will be particularly hard hit by this crisis—and they represent approximately 90% of private sector firms and generate more than half of the jobs in developing countries. Hence the World Bank Group plans to release revisions to the Principles for Effective Insolvency and Creditor/Debtor Regimes with a focus on SME insolvency by the end of June 2020.