Two months into the COVID-19 pandemic, the Centers for Disease Control issued a recommendation that commuters avoid mass transit altogether. Instead, people could drive themselves to work, and employers could compensate them with parking perks.

It was a “let them eat cake” misstep. Not everyone can afford a car, nor can they spring for taxi fare or a rideshare. And clogging our city streets with automobiles causes pollution and increases the likelihood of traffic accidents. And, as with many early pieces of guidance formed without a full understanding of the virus, the recommendation may have been offbase. Study after study has since found that there is very little risk to riding public transit — where, at least in larger cities, masks have been largely mandated — and there have not been any significant widespread infections that originated on a subway, bus or train.

Nevertheless, the initial message — that mass transit poses a health risk — wrapped its tendrils around the public mindset and has been causing damage ever since. In early March 2020, buses, trains and subways in the U.S. were 98% full. But demand nosedived to below 20% that month and hovered around one-third capacity for the following year; since then, it has slowly risen to about 60% capacity, according to the American Public Transportation Association.

As a result, public transit agencies, which rely on farebox revenue to cover the bulk of operating costs, suffered financial catastrophe. Many have yet to recover, leaving them unable to afford basic functions, such as maintaining or expanding service levels and repairing infrastructure. Despite their best efforts, many agencies were sometimes unable to provide adequate coverage during the pandemic’s darkest days.

As part of the larger effort to bring people back to downtowns still struggling to recover from the pandemic, it has become increasingly important to support mayors and local leaders with the various obstacles related to reinvigorating mass transit ridership, including public safety concerns.

There are some glimmers of hope. Federal aid has eased the urgency of the financial crisis for many transit systems. Also, the APTA data shows that weekend ridership is edging closer to pre-pandemic patterns, perhaps evidence that “leisure” riders are venturing back. And continued strength in ridership in lower-income neighborhoods has helped stabilize the bottom line.

Tap-and-go transit

A decade ago, Transport for London became the first mass transit system to introduce contactless fare payments using a rider’s own bank card. Now such tap-and-go payments can be made from cards or mobile phones in hundreds of cities around the world – from New York City subways to Milan trains to Sydney ferries.

In February, Bangkok’s Metropolitan Rapid Transit became the latest city to adopt contactless ticketing through a partnership with Mastercard and Krunghthai Bank. Riders use their bank cards to tap and go, eliminating the need for buy tickets or top up transit cards. Ticketless transit also benefits tourists, who don’t have to struggle to navigate a new city’s closed-loop smartcard system.

The only surefire way to bolster revenue — and ultimately improve service — is to get all mass transit riders back on board. That could start with finding ways to connect with the new brand of office employee who works remotely several days a week. Instead of offering a monthly pass, agencies could sell “hybrid worker passes” that would cover rides for 8 to 14 days over the course of a month. As agencies get more creative, state governments would need to help by removing the red tape associated with pricing change approvals.

Cities and towns can look to partner with event marketers (who have also been struggling) or theater companies or other local festivals and activities. They could bundle a ticket to a show with a train ticket or offer a discount to a sports event with a group rate. Several state fairs across the country already provide such deals to ease parking at their venues or keep people safe who may be drinking. By building a case for car owners to choose public transit, agencies can bring dollars back into the system.

The federal government could also allocate funding to help with backlogged maintenance. Not only will this spending improve rider safety, but upgrades to a train or bus station boosts rider’s confidence. When a broken elevator or escalator is fixed or a new coat of paint helps brighten up a station, there is the perception that the rider’s needs are important and being met. And there is continued momentum for digitizing the transit experience, such as tap-and-go fare collection.

And lowering prices always wins people over. Cheaper transportation options are especially attractive given the recent rise in gas prices. Chicago has reduced fares on its system while New York will freeze fares for the next year. New York’s MTA also added additional police patrols after some higher profile crimes on the subway system to make sure riders feel safe.

Tap on phone for ticketing

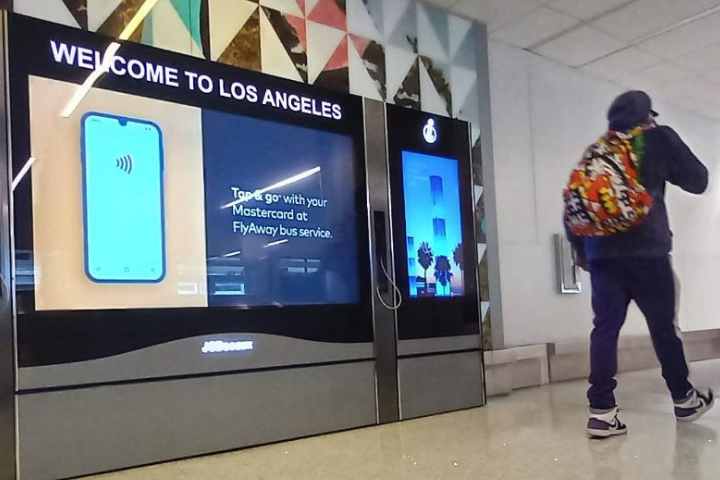

Smaller transit operators can struggle with the cost of digital infrastructure upgrades often needed for contactless ticketing. But there’s an easier way to bring the convenience of contactless travel to riders. At Los Angeles International Airport, Mastercard and Pacific Coast launched a pilot in which Flyaway bus shuttle operators use an Android smartphone app powered by Mastercard’s Cloud Point of Sale technology to accept fares from any mobile wallet-equipped device or contactless card. The pilot was recently extended following increasing rider adoption and positive agent feedback.

“One agent told us it works at lightning speed, and another called it a game changer, helping eliminate lines and getting passengers on their way faster and with a minimum of fuss,’’ says Troy Dennis, a Mastercard senior vice president for Product.

Finally, given mounting concern over climate change, it’s always beneficial to remind people that using fewer single-occupancy vehicles reduces fuel, air pollution and a region’s carbon footprint.

Sadly, the people who bear the brunt of this decline in service are those who’ve been supporting mass transit all along: the city’s most vulnerable residents. These are folks who don’t have a car or other means of reliable, inexpensive travel. And many are also the essential workers who have been making sure the rest of us are OK. According to TransitCenter.org, workers classified as “essential” during the pandemic account for 36% of total transit commuters in the U.S. These are the people who provide us with health care, child care, medicine and groceries.

It’s time for transportation agencies to transform recent challenges into an opportunity to rethink how mass transit functions within society. By introducing a dynamic system with new planning, new pricing, new innovations and partnerships, agencies can “future proof” themselves and continue to be at the heart of society.

One card to rule them all

The pandemic accelerated the shift to digital, with cities embracing digital delivery of services and the ability to make paperless disbursements, ensuring more equitable access to the digital economy for their residents. Mastercard City Key is a customizable payment program that allows cities to integrate payments, disbursements, access to city buildings and mass transit on one contactless card. In the Czech Republic’s Kolin, all students have access to public transportation, school entry, library services and can pay for their school lunches through the Smart Keychain launched by Mastercard, Paynovatio and CSOB.