Earth is warming at an unprecedented rate, with the last decade being by far the warmest one on record. The severe implications of the implied climate change have made the green and sustainability imperatives clearer than ever. Countries around the world have accordingly made new commitments and taken action to fight climate change, often setting more ambitious goals to achieve net-zero emissions. By end 2021, net-zero pledges have been estimated to cover 65% of global emissions. In the same line, governments as well as businesses have introduced initiatives to standardize and enhance climate-change disclosures.[1]

According to recent studies, foreign direct investment (FDI) can have positive environmental effects in host economies. From a policy point of view, the question is: what investment attraction policies, in general, and IPAs –as agencies at the forefront of such policies—, in particular, can and actually do to help materialize such FDI positive environmental potential?

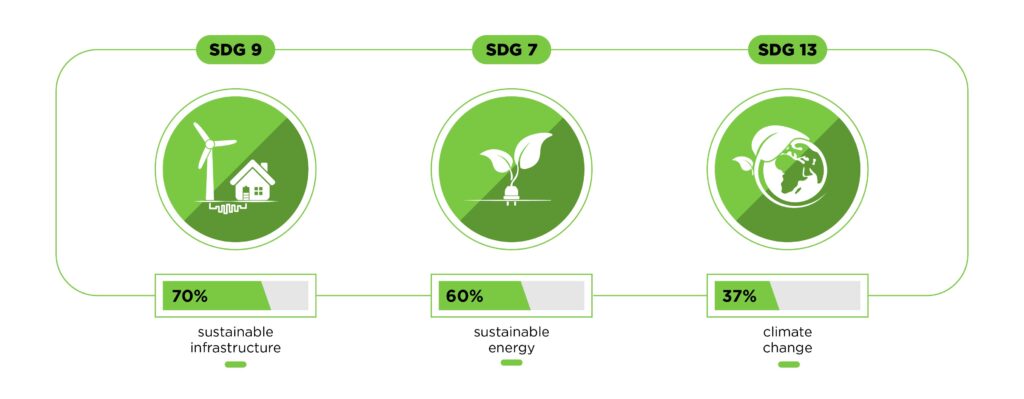

Besides their goal of generating and facilitating more investment, IPAs are increasingly asked to attract investors that are sustainable, inclusive, and green. According to an OECD survey conducted in 2021, 37% of OECD IPAs report to contribute to the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 13 related to climate change. Higher shares report to contribute to broader SDGs that could also be related to green investment (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Share of IPAs Reporting to Contribute to Climate-Related SDG

Yet, aspiring to do good and doing good cannot be the same things. Establishing to what extent this is the case requires measuring the environmental implications of IPAs’ actions.

What Do We Know?

Some basic tools can help IPAs measure the potential climate contribution of assisted investment projects. For example, data on green-house gas (GHG) emissions by sector are collected in many countries. They are also compiled for several countries by international and non-profit organizations and are publicly available (e.g., UNHCC, 2022; OECD, 2022; or Climate Watch, 2022).[2] Combined with the internal data available to most IPAs on their assistance of firms, they help establish if IPAs indeed focus on assisting firms in less-polluting industries. Moreover, when also merged with information on the presence of multinational firms’ foreign affiliates in their countries from local administrative sources or private providers, data on sector-level emission makes it possible to determine if the impact of IPA assistance is higher in such industries. This is exactly what the IDB has done in a recent flagship report on investment promotion for 12 Latin American and the Caribbean (LAC) countries.[3]

What did we learn from such an analysis?

- IPAs tend to focus on firms in less polluting sectors: 60% of multinational firms assisted by IPAs were in relatively less-polluting sectors

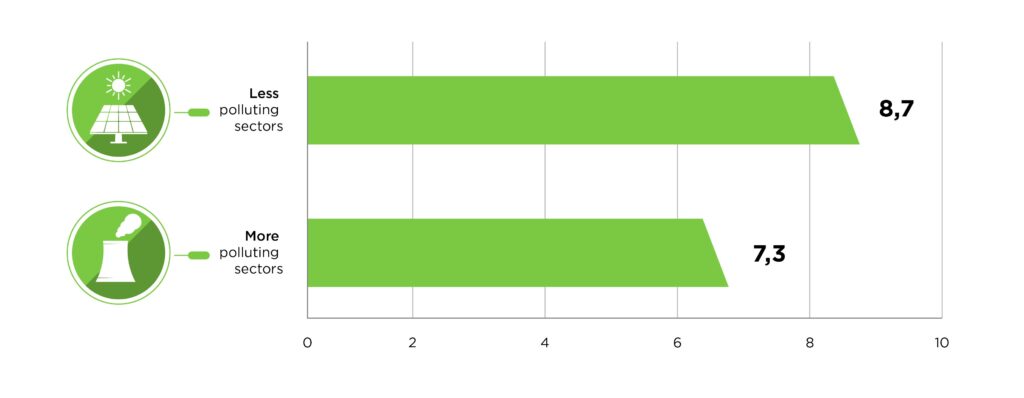

- Investment promotion favors the entry of firms in relatively less-polluting sectors (Figure 3).IPAs increased the probability of first entry by a multinational firm in such sectors by 8.7 percentage points, on average.

Figure 2

IPAs’ Assistance Favors Entry of Multinational Firms in Sectors with Less CO2 Emissions

What Can Be Done?

This simple exercise provides IPAs with additional insights. Yet, much more can be done. For example, IPAs may attempt to obtain firm-level information from several different sources to measure the environmental performance of multinational firms, both assisted and established, as well as potential spillovers on domestic counterparts:

- In some countries, IPAs may be able to gain access to administrative data on firm-level emissions, energy consumption or other relevant variables, for example, from environmental protection, certification, and emission-disclosure monitoring bodies.[4] An example in this regard is Chile’s Register of Emissions and Transfers of Pollutants. IPAs can also use or complement such data with their own data-gathering, or develop proxies based on their correlation with the official statistics.

- Second, private data providers offer environmental, social and governance (ESG) scores and underlying data of firms. While it has been shown that E-scores themselves do not necessarily correlate with emission reductions, and can vary widely, ESG-score providers increasingly dispose of actual and estimated CO2 emissions.[5] They can also be complemented with data from organizations that assist firms in complying with climate disclosure requirements.[6] Such data may provide useful insights at least for the largest and publicly traded firms.

The rise in climate-change policies worldwide is likely to require IPAs to adopt and develop new tools to measure green investment in the future. While far from being invisible today, more can be done. The IDB, through its Integration and Trade Sector, is supporting LAC IPAs in coping with this challenge and is currently developing a consistent FDI sustainability monitoring and evaluation approach, which includes an evidence-based scoring mechanism.