The pandemic does not come to the region in good time, the little dynamism of growth in recent years generates uncertainty of the outlook for the future. For 2020, the consensus among analysts expects a drop in output in Latin America and the Caribbean between -2% and -6%, which comparative terms would be deeper contractions than the debt crisis of the eighties (-2.4%) and the international financial crisis (-2.1%). If this materialized, it would be the strongest recession in the last 60 years.

The nature of the shock is mixed as it is a combination of supply and demand. The pandemic has generated a slowdown in external demand explained by a drop in exports to the United States, Europe and China. On the other hand, it is a supply shock since it directly affects the job offer and in response as a measure to contain the crisis, it is necessary to temporarily close companies and businesses.

From the fiscal point of view, many questions arise. Do we have fiscal space to attend to the crisis? What is the possible impact on public finances? What economic policy guidelines must be taken to reestablish the path of fiscal sustainability?

Limited fiscal space

The region in the last decade has been immersed in a process of fiscal consolidation. Most of the countries have established fiscal responsibility laws, medium-term fiscal frameworks and fiscal rules which have increased the fiscal institutionality of the region. Institutionality has been tested on several occasions, for example, during the international financial crisis and the drop in oil prices between 2014-2016.

Despite the fiscal efforts made, this shock is framed in a context of little fiscal space in the region. Characterized by the low performance of economic growth and the persistence of the fiscal deficit, which contrasts with advanced economies in which, despite large increases in public debt, interest rates are low and therefore have more margin for maneuver. Thus, at the end of 2019, 60% of the countries in the region showed debt levels greater than 40% of GDP and fiscal adjustments ranging between 2% and 7% of GDP.

The current governments have responded by increasing their budget to address the crisis, on average the budget increase in the region is equivalent to between 2.4% -3.3% of GDP[1]. In the current circumstances, a fiscal stimulus is necessary, but at the same time, financing conditions deteriorate. Risk premiums have increased substantially, by more than 600 basis points (bps) on average so far this year. The economies have experienced strong depreciations that increase the value of debt in foreign currency and have seen a substantial decrease in their access to debt markets.

Scenarios of fiscal impact on the region

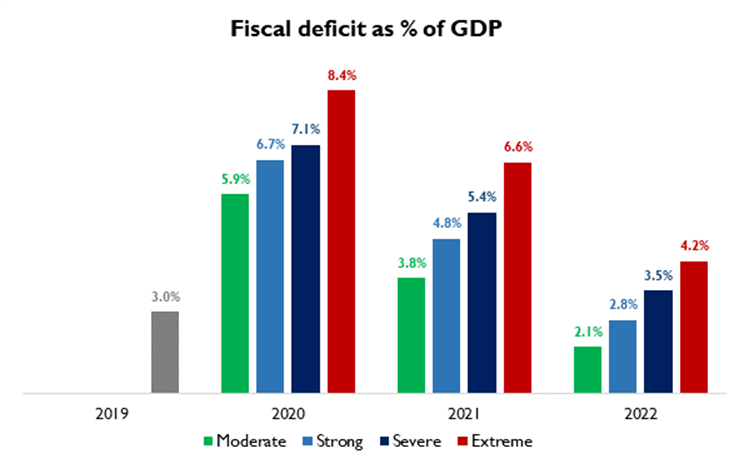

As for fiscal balances, a deterioration is expected, explained by the increase in spending, a drop in growth and a drop in tax revenues. Based on the estimates of the IDB’s macroeconomic report (2020), activity is expected to contract at rates that would range on average in the next three years from 0.3% to -3.4%. With deep contractions of GDP growth in 2020, they could reach between -2% to -6% approximately, deteriorating tax revenues and with higher borrowing costs due to increased risk premiums. Consequently, the fiscal deficit would increase in the short term between 1 percentage points (pp) to 3.4 pp of GDP[2] . Regarding public debt, although in recent years an increasing behavior was appreciated, it is estimated that it would continue on an upward path, but even more pronounced and persistent in the medium term (figure 1).

Figure 1. Forecast on fiscal balance and gross debt

Source: IDB-FMM estimates

Fiscal sustainability in the medium term

The persistence of the shock in the region leads to an accumulation of fiscal imbalances that can undermine economic growth and medium-term fiscal sustainability. It is important to mention that these forecasts are under the assumption that no forward post-pandemic fiscal measure is carried out

Medium-term adjustments are necessary to regain the path of fiscal sustainability, and this may be a particularly greater challenge for countries with less fiscal space, which face the tradeoff between the cost of future fiscal adjustment versus the economic cost of possibility of debt default events and / or financial crises.

Sudden stop in capital flows

The increase in the cost of indebtedness of the countries is also reflected in a sudden stop in the flow of capital to emerging countries. This is evidenced by a fall in foreign investment in securities (private and public) that has exceeded what was observed in the 2009 global financial crisis [3][3]. This occurs in a context where, on the domestic debt side, LAC’s financial markets in recent years have deepened financially, expanding its investment base to foreign holders. For example, countries such as Peru, Colombia, and Mexico at the end of 2019, nonresident holders of domestic bonds averaged a third.

This sudden stop of capital flows to LAC increases financing needs due to the effects of a substantial real depreciation (Cavallo 2020). For the region’s average economy, the variation in the real exchange rate necessary to balance the external deficit is greater than 20%[4].

The effects of this sudden real depreciation on public finances can be significant. In particular, the effect occurs through higher amortizations and interest on debt in foreign currency. Figure 2 shows that the effects of different scenarios of decline in economic activity and increase in interest rates (measured in bps) would imply increases in additional resources that could reach up to 6% of GDP in a scenario of strong contraction of output and substantial increase in the interest rate.

In this way, the region faces the crisis starting from a vulnerable fiscal situation, where the fiscal consolidation process has stagnated in recent years, and with most countries with few degrees of freedom or with a substantial deterioration of public finances. The effect of the pandemic would translate into possible increases in the deficit in 2020 up to 8% of GDP and 4% of GDP in the medium term. Consequently, public debt could reach levels of 65% of GDP in 2020 and with an increasing path of around 75% in the medium term.

In order to achieve debt stabilization and improve the region’s fiscal position, it will be necessary in a post-pandemic context for economic activity and fiscal revenues to grow faster than the accumulation of past deficits.

What to do forward to ensure fiscal sustainability?

Thus, to return to the path of fiscal sustainability, it is necessary to establish mechanisms so that increases in spending are transitory and do not become budgetary rigidities later on.

Background that is evident from the 2008/2009 global financial crisis. This includes the multiple tax exemptions, expenses and contingent liabilities[5] that may appear in response to the crisis. The task is not simple, since the fiscal adjustment must be gradual without sacrificing the trajectory of the economic recovery.

At the same time, it is necessary to prioritize fiscal transparency in terms of recognizing the magnitude of the shock in fiscal balances and public debt, also in operations outside the budget and quasi-fiscal such as the capitalization of guarantee funds and other types of expenses intended to support the private sector (such as partial payment of the payroll and loan guarantees).

Complementarity between tax authorities and tax councils / regulatory committees should go a long way towards making the magnitude of the shock transparent and a fiscal consolidation plan in the medium term. All these measures would allow correction mechanisms towards a path of fiscal consolidation in the face of increases in debt and deficit.